Like a lot of programmers out there, I started off by learning my first language at a very young age and completely out of curiosity. My first few projects were personal web development and PHP server-side coding. It was easy to get started because almost anyone could obtain a free web hosting account. All you had to do was let the hosting company put popup ads on your site. Ah the days before popup blockers. There was so little friction to learning and enhancing one’s coding abilities that I quickly developed the skill-sets needed to be successful in the software industry. It helped me tremendously when I started looking for co-op placements in my first few years of undergrad.

But I had one issue. It goes like this.

The more languages and platforms I learned, the less black box-ish things were becoming for me but…well let me start with an example. When I started learning Linux, I understood why Git and SVN seem so foreign on Windows. It’s because they are from the Linux world where it is so much easier to do a lot of things on the shell and Windows is all GUI based. And the shell isn’t really a black-box either, you can build your own shell using C and a few hundred lines of code. And the OS it’s running on isn’t a black-box either—you can crack open the kernel source code and view the C code. If you have had any experience with OS161 and MIPS, you’ll know that a basic operating system isn’t rocket science. But where was all this going towards? Now that I understood what was happening at the kernel level, what was next? I did not realize the biggest black-box for me was the computer hardware. Not just the computer hardware, but all hardware. Electricity, transistors, logic gates, the real deal.

I’ve always shied away from anything related to hardware. Microcontroller you say? What’s that? Something to run little programs on to control sensors, motors, and lights? Didn’t know, didn’t care. I felt like I had everything I needed in software and the rest can be dealt with by the computer/electrical engineers. Boy was I wrong.

This semester of my computer science undergrad at the University of Toronto, I’m enrolled in a computer organization course which has been absolutely eye-opening. It is a new professor and he has completely redone the course. Much of the course is hands-on/lab based and the labs are almost entirely in Verilog. The Verilog code is used to program the FPGA (DE2) boards and test out the programs using LEDs, switches, keys, etc. I enjoyed the labs very much but didn’t really expect to do any further hardware programming after graduation. It wasn’t until I saw this video of a project using the DE2 board that gave me an epiphany and the reason for this article. Basically the project connected a 40-pin cable from the DE2 board to a breadboard which was then used to interface with actual hardware components like motors to drive a toy tank. I wondered, “Can you program anything that simply? I could prototype a set of servo-motors to open the blinds in my room! I could use multiple sensors to more precisely control the climate in my room! I could do anything! Live and real! Things that move, make noises, light up. Not just stuff on a computer screen!” And then there was this huge domino effect of ideas and realizations.

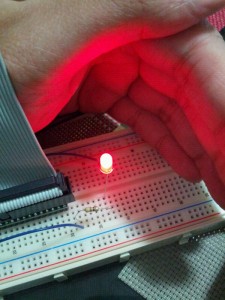

My very own “hello world” for hardware. The 40-pin cable is connected to the GPIO ports of the DE2-70 FPGA.

My very own “hello world” for hardware. The 40-pin cable is connected to the GPIO ports of the DE2-70 FPGA.

My innate desire for innovation felt like it just leveled-up. All of a sudden at my disposal was a new dimension of tools. My wireless thermostat’s receiver blew this summer when trying to turn on the AC. No problem, because I WILL MAKE MY OWN NOW. As of this writing, I’m in the middle of the final project for this course. I am building a laser targeting game that uses 2 x-y servo-motors to move a laser that is controlled by a joystick. This project has me very excited and the components are coming along really well. I can’t wait until I get more free time to play with hardware after this, especially those tiny microcontrollers that cost like barely anything.

Hardware isn’t all pretty though. There are lots of things that can go wrong, especially because you’re dealing with electricity, which can fluctuate. This is why software people, like me, can shy away from hardware initially. Software is perfect. If x is 1 and y is 1, adding x and y will always give you 2. In hardware, that might not work out (especially depending on how you implement your circuits). Once you get past the fear of uncertainty though like I did, you’ll be amazed at just what depth one can dive into in hardware. I think this fear of uncertainty contributes to the barrier-to-entry and is the reason why we don’t see an equal number of breakthroughs in hardware as we are seeing in software (consider how rapidly the world of app development is expanding as opposed to gadget development).

I feel that the software realm is quickly becoming saturated. I hope I’m wrong but it doesn’t help that there are tons and tons of apps out there today for even the most mundane things. The time has passed to easily innovate in the app space. But you know what I think is still ripe for innovation? Hardware. Gadgets. Cool stuff that do things wirelessly. Stuff that builds the physical platform for software to further innovate on. If you’re like me and have a relentless desire for innovation, get yourself a microcontroller or an FPGA and build something. You will solve what I think is one of the greatest black-boxes, computer hardware. And you will bring together components for a living, breathing, machine—to run your software on :D.